By: Shannon Davila, MSN, RN, CPPS, CPHQ, CIC, FAPIC

Executive Director of Total Systems Safety, ECRI

Veteran of the United States Air Force

Jackie is a 39-year-old woman who has recently moved to a new town. She contacts the local health care system and makes an appointment to see a health care provider. On the day of her appointment, Jackie completes the check-in process, including the usual intake forms about her physical health, allergies, and medications. Once in the exam room, the provider briefly introduces themself and begins to review Jackie’s medical history.

The visit is brief; Jackie appears to be healthy with no medical issues and no significant family history of disease. At the age of 39, there are no major screenings recommended (eg, a mammogram). The provider does not see the need for any additional follow-up testing and asks Jackie to schedule her annual checkup for the next year.

However, the provider was not aware that Jackie served in the US Army and was deployed to Afghanistan. Jackie was a mechanic in the Army; during her deployment, she worked every day in a hangar that was downwind from one of the base’s burn pits. The base commonly used the burn pit to destroy trash and other waste. Jackie’s exposure to the toxic chemicals emitted from the burn pit created a serious and potentially deadly risk for her—a risk that could lead to undiagnosed disease, including cancer, if left unevaluated.

Unfortunately, the provider did not know about Jackie’s military service because the health system did not have a process to collect that information or a way to alert health care providers of patients’ veteran status. Additionally, the provider was unaware that women veterans under age 40 who may have been exposed to burn pits and other toxins during their service may be eligible for breast cancer screening and mammograms at a United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center.1

This scenario illustrates a disparity in the standard of care that may affect millions of veterans who seek health care outside of the VA health system. According to a National Health Statistics report, in 2021, there were approximately 19 million veterans in the United States, with more than 9 million of them enrolled in VA health care.2 A lower percentage of post-9/11 (September 11, 2001) veterans enrolled in VA health care than all other veterans, and of those enrolled, post-9/11 veterans used VA health care at a lower rate than all other veterans.3 To complicate matters, there is a lack of adequate training for civilian health care providers on how to properly assess the health needs of veterans. A study by the Association of American Medical Colleges showed that, among over 100 medical schools, only 31% included content about cultural competence for military service members or veterans in their graduate curriculum.4

Unique Health Needs of Veterans

Veterans face complex health issues that can include both physical and emotional injuries resulting from their military service. The environment in which military service personnel live and work can create risks for a wide array of health conditions. Without an effective process to assess these risks, health care providers are potentially missing opportunities to properly diagnose and treat veterans.

According to a 2019 Pew research study,1 in 5 veterans have been seriously injured during their military service.5 Among veterans who have been deployed, 23% experienced a negative impact on their physical health, and 23% experienced a negative impact on their mental health. Sixty-one percent of veterans have been deployed at least once, while nearly 30% were deployed 3 or more times, with post-9/11 veterans having a higher deployment rate compared to those who served prior to 9/11.

Physical injuries that veterans can sustain while in service include noncombat musculoskeletal injuries, exposure to hazardous materials, and combat-related injuries like loss of limbs, hearing and vision loss, burns, and traumatic brain injury.6 Military veterans also struggle with service-related emotional injuries, which can manifest as a variety of different mental health conditions. In 1 study, 28% of OEF/OIF/OND veterans (ie, veterans who served since September 11, 2001, in Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Iraqi Freedom, and Operation New Dawn) self-reported that they had received at least 1 mental health diagnosis in the previous 24 months.7

It has also been shown that health disparities exist within the veteran population. For example, Black and Hispanic veterans are more likely to be diagnosed with mental health, musculoskeletal, and infectious disease conditions than White veterans; female veterans have higher rates of depression than their male counterparts; and according to an analysis of measures of health care access, quality, and disparities, veterans age 65+ experienced better care than veterans ages 18-44 across half of the categories.8-10

Taking a Total Systems Approach to Improving Veteran Health

Health care disparities that lead to missed diagnostic opportunities for veterans cannot be tolerated. By infusing principles of system design, human factors, advanced safety science, and health equity, a total systems approach to safety can create greater efficiency and resilience in clinical and safety operations that directly impact patients. Using this approach, leaders in both civilian and VA health care should examine the system factors that contribute to failures in the assessment and management of veterans’ unique health needs.

These failures can occur at multiple levels of the health care system, including the internal environment (eg, when providers fail to ask about the patient’s military service during the provider-patient interaction) and the external environment (eg, when educational institutions do not prepare nurses, physicians, and other clinicians to adequately assess and treat veterans’ unique health needs). As depicted in Figure 1, correcting these failures requires redesigning the physical care environment, evaluating the tasks and processes performed to deliver care, and developing tools and technology that support the organization and the people who make up the work system, including providers, patients, and families.

Figure 1. Total Systems Safety Framework

SALUTE Program to Foster Connections between Veterans and Providers

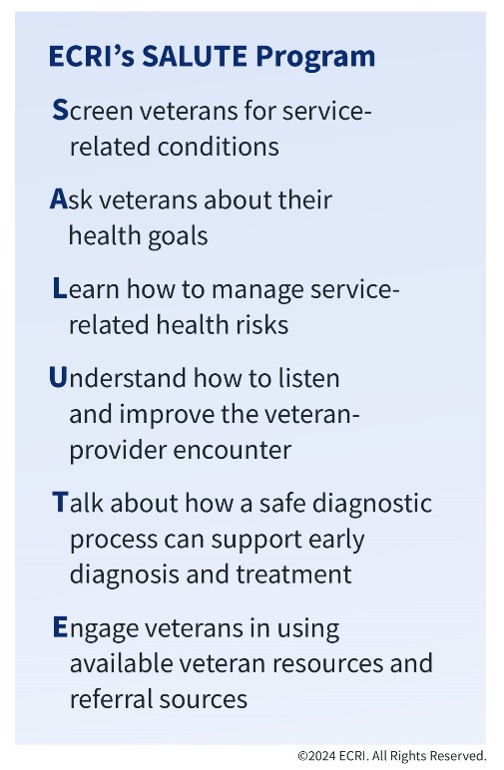

To assist health care providers in the redesign of care provided to veterans, ECRI has launched the SALUTE Program and invited individuals and organizations to actively engage military veterans, their families, and caregivers as partners in safety.

This partnership is a core component of ECRI’s Total Systems Safety approach and is essential to improving diagnostic safety.

As shown in Figure 2, by adopting ECRI’s SALUTE Program, health care organizations can redesign the provider-patient interaction and integrate evidence-based tools to help in the following ways:

— Empower military veterans to become stronger advocates for their own health needs by using the Be the Expert on You: For Those Who Have Served in the Military pre-visit preparation tool; and

— Support health care providers in making more accurate assessments, diagnoses, and treatment plans for individuals who are at higher risk of service-related injuries with the 60 Seconds of Listening to Improve Diagnostic Safety for Military Veterans training slides.

Figure 2. ECRI SALUTE Program

Based on the Toolkit for Engaging Patients To Improve Diagnostic Safety, created by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, these easy-to-use tools create an opportunity for veterans and health care providers to have important conversations about the patient’s military service and potential service-related health risks.11 They allow the provider to listen to and assess important information through screening questions and discussion. Based on the veteran’s health goals, the provider can make recommendations for next steps, including diagnostic testing. For veterans who are interested in learning about potential VA health benefits, they can be directed to the appropriate resources.

To learn more about SALUTE, visit https://home.ecri.org/pages/ecri-salute-program.

REFERENCES

- VA expands breast cancer screenings and mammograms for veterans with potential toxic exposures. VA News. July 27, 2023. Accessed August 30, 2024. https://news.va.gov/press-room/breast-cancer-veterans-toxic-exposures/

- Cohen RA, Boersma P. Financial burden of medical care among veterans aged 25–64, by health insurance coverage: United States, 2019–2021. National Center for Health Statistics. March 22, 2023. Accessed August 30, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ nhsr/nhsr182.pdf

- National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Profile of post- 9/11 veterans: 2016. March 2018. Accessed August 30, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Post_911_Veterans_Profile_2016.pdf

- Krakower J, Navarro AM, Prescott JE. Training for the treatment of PTSD and TBI in U.S. medical schools. Association of American Medical Colleges. November 2012. Accessed August 30, 2024. https://www.aamc.org/media/5966/download

- Parker K, Igielnik R, Barroso A, Cilluffo A. The American veteran experience and the post-9/11 generation. Pew Research Center. September 10, 2019. Accessed August 30, 2024. https://www. pewresearch.org/social-trends/2019/09/10/deployment-combat-and-their-consequences/

- Molloy JM, Pendergrass TL, Lee IE, Chervak MC, Hauret KG, Rhon DI. Musculoskeletal injuries and United States Army readiness part I: overview of injuries and their strategic impact. Mil Med. 2020;185(9-10):e1461-e1471. doi:10.1093/milmed/usaa027

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Committee to Evaluate the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health Services. Evaluation of the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health Services. National Academies Press; 2018. Accessed August 30, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499497/

- Williams L, Pavlish C, Maliski S, Washington D. Clearing away past wreckage: a constructivist grounded theory of identity and mental health access by female veterans. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2018;41(4):327-339. doi:10.1097/ANS.0000000000000219

- National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report Chartbook on Healthcare for Veterans. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; November 2020. AHRQ Pub. No. 21- 0003. Accessed on August 28, 2024. https://www.ahrq. gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/chartbooks/veterans/index. html?utm_content=&utm_medium=email&utm_name=&utm_ source=govdelivery&utm_term=

- Ward RE, Nguyen XT, Li Y, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in U.S. veteran health characteristics. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(5):2411. doi:10.3390/ijerph18052411

- Toolkit for engaging patients to improve diagnostic safety. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Reviewed July 2022. Accessed October 4, 2023. https://www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/settings/ ambulatory/tools/diagnostic-safety/toolkit.html